Recently, I saw an exchange on Twitter that triggered me to think about what it means for an argument to “beg the question” against some position. The whole issue is tricky, but it’s important to understand what makes an argument good. I think it is very easy to be misled when thinking about this and I’d like to share some thoughts.

So, first, let’s start with a paradigmatic example of a question-begging argument. Suppose you are a nuclear-enthusiast: you think nuclear energy is the best form of energy. Suppose I am a solar-enthusiast: I think solar energy is the best form of energy. I make the following argument to try and convince you:

(1) If nuclear energy is the best form of energy, then 1+1=3

(2) It’s not the case that 1+1=3

(3) So, it isn’t true that nuclear energy is the best form of energy.

This seems like a pretty absurd argument. But why is it bad? The argument is valid (if the premises are true, the conclusion follows). Is the argument bad because one of the premises is false? Well, that’s not so easy to determine. If solar is the best form of energy, then (1) would in fact be true. And maybe solar really is the best form of energy. The premises are not clearly false.

So what makes this argument a bad argument? What makes this argument bad is that it shouldn’t convince anyone of anything. Why would anyone believe (1) is true? Well … as we said above, it might be true, if nuclear energy isn’t in fact the best form of energy. But, if you and I are going to try and figure out whether (1) is true, what do we have to settle? We have to settle whether nuclear energy is the best form of energy or not! In other words, we have to settle our original debate!

So, this argument did nothing. We were having a debate about whether nuclear energy is the best form of energy. I then gave an argument, whose key premise depends entirely on whether you think nuclear energy is the best form of energy. The argument I gave basically just asks the same exact question we were debating about. That is what it means for an argument to “beg” the question: it simply gives rise to literally the exact question at issue.

That isn’t what good arguments are supposed to achieve. Good arguments are supposed to give rise to different, less contested questions. Let me give you an example. Suppose you and I are arguing about whether it is rational to have intransitive preferences (i.e., preferring A to B, preferring B to C, but preferring C to A). You point out that, if someone has intransitive preferences, they can be money pumped: if you start out having C, I could get you to pay me 1 dollar to replace it with B. I could then get you to pay me 1 dollar to replace it with A. But then I could get you to pay me 1 dollar to replace it with C! I can get you to pay me 3 dollars to end up at the exact position you started in!

But it seems like no rational agent should be able to get money pumped. So, no rational agent should have intransitive preferences. The argument:

(1) If you have intransitive preferences, you can get money pumped

(2) No rational agent can get money pumped

(3) So, no rational agent has intransitive preferences.

What makes this a good argument? Well, even if (2) is false, what makes this a good argument is that it makes dialectical progress. You and I started out by arguing about whether intransitive preferences were rational. This argument moves things forward by shifting our focus to a new issue: can it be rational to be money pumped? You and I might have diverging intuitions about transitivity, but we might have converging intuitions about money pumps. We might both agree, on this new issue, that no rational agent can be money pumped. And that agreement, this argument shows, is enough to show that we should also agree that intransitive preferences are irrational.

This is what good arguments do: they move things forward, by showing that there are other, independent considerations that should move you towards my side.

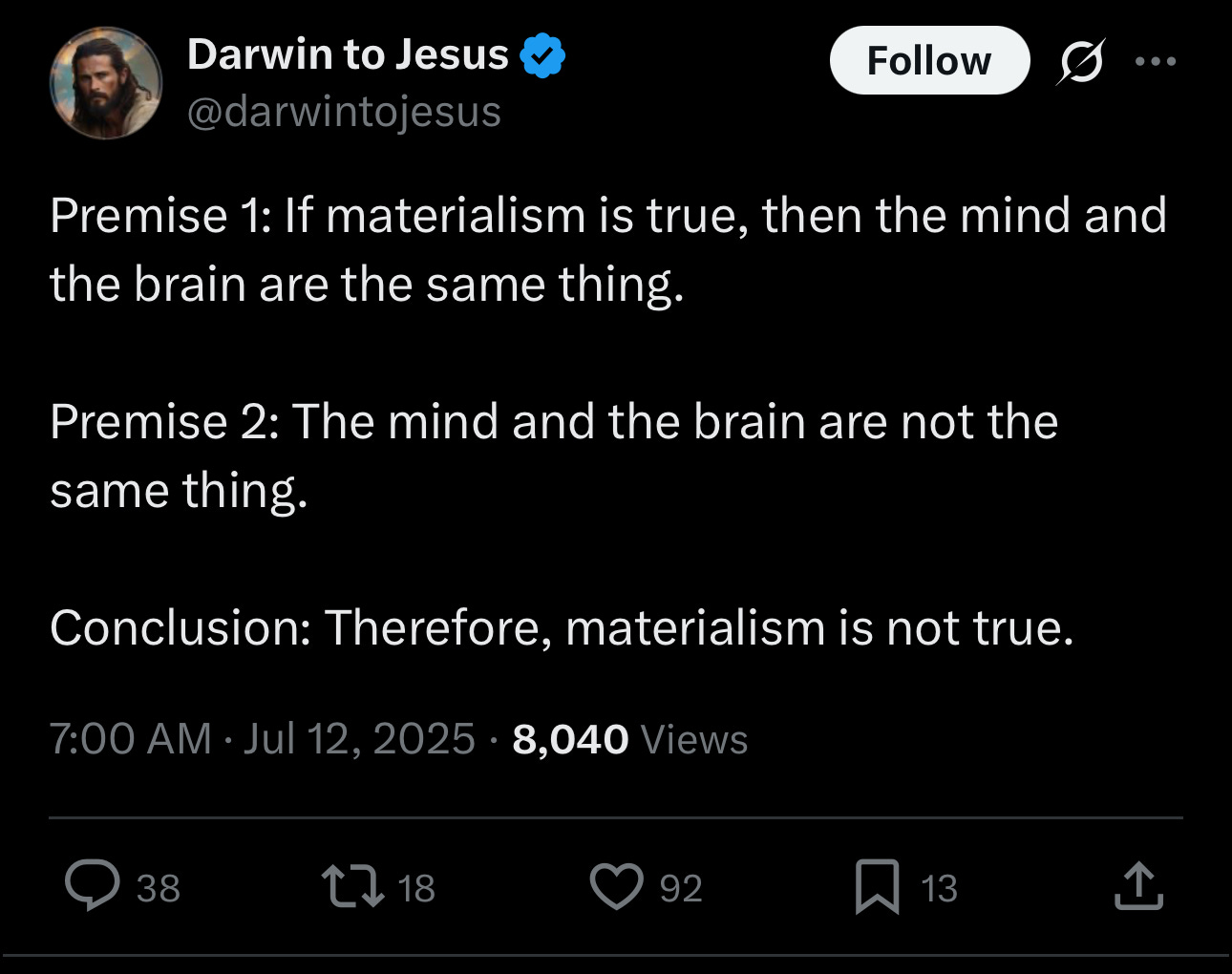

Now, with all that said, here’s the Twitter exchange that sparked my interest. A popular account posted the following argument against materialism (the view that all things are material/physical):

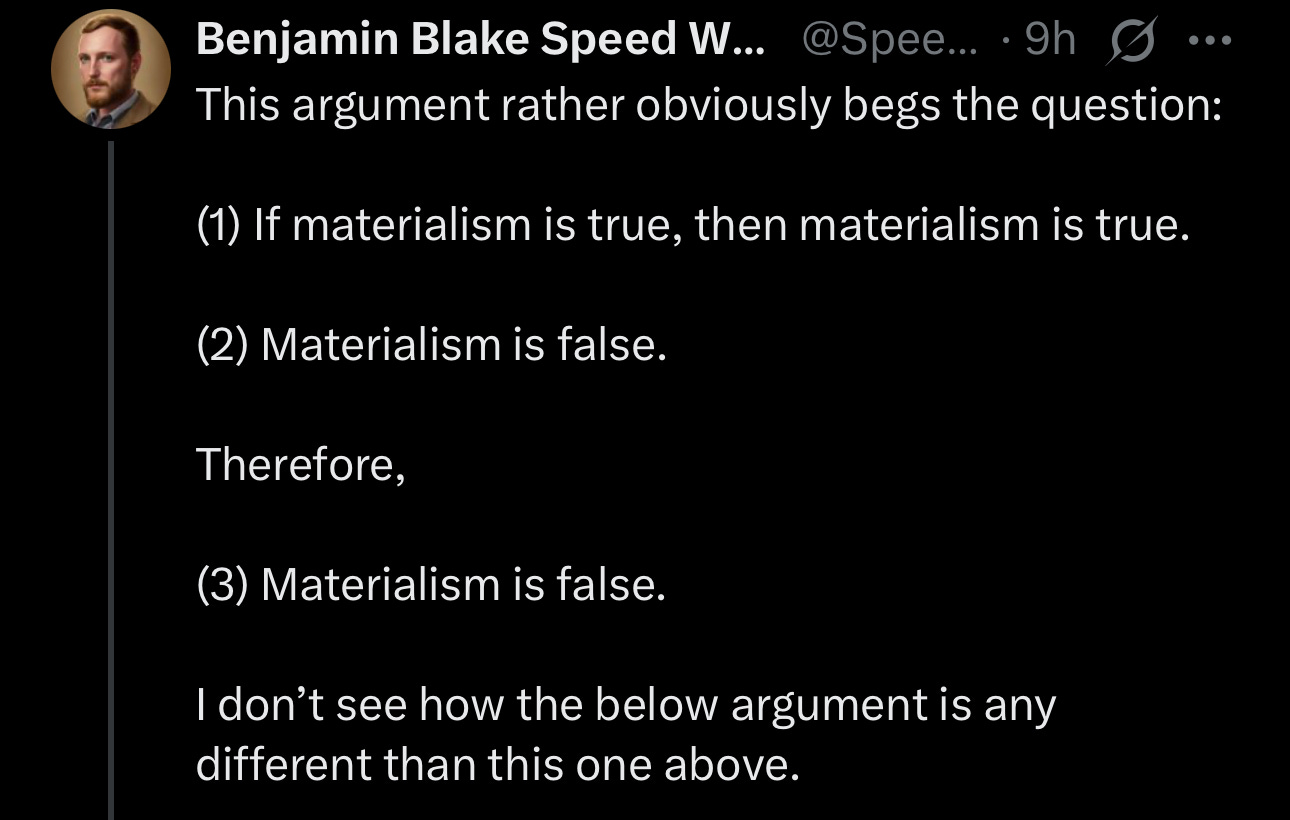

Ben Watkins, a wonderful person and friend, then responded with this:

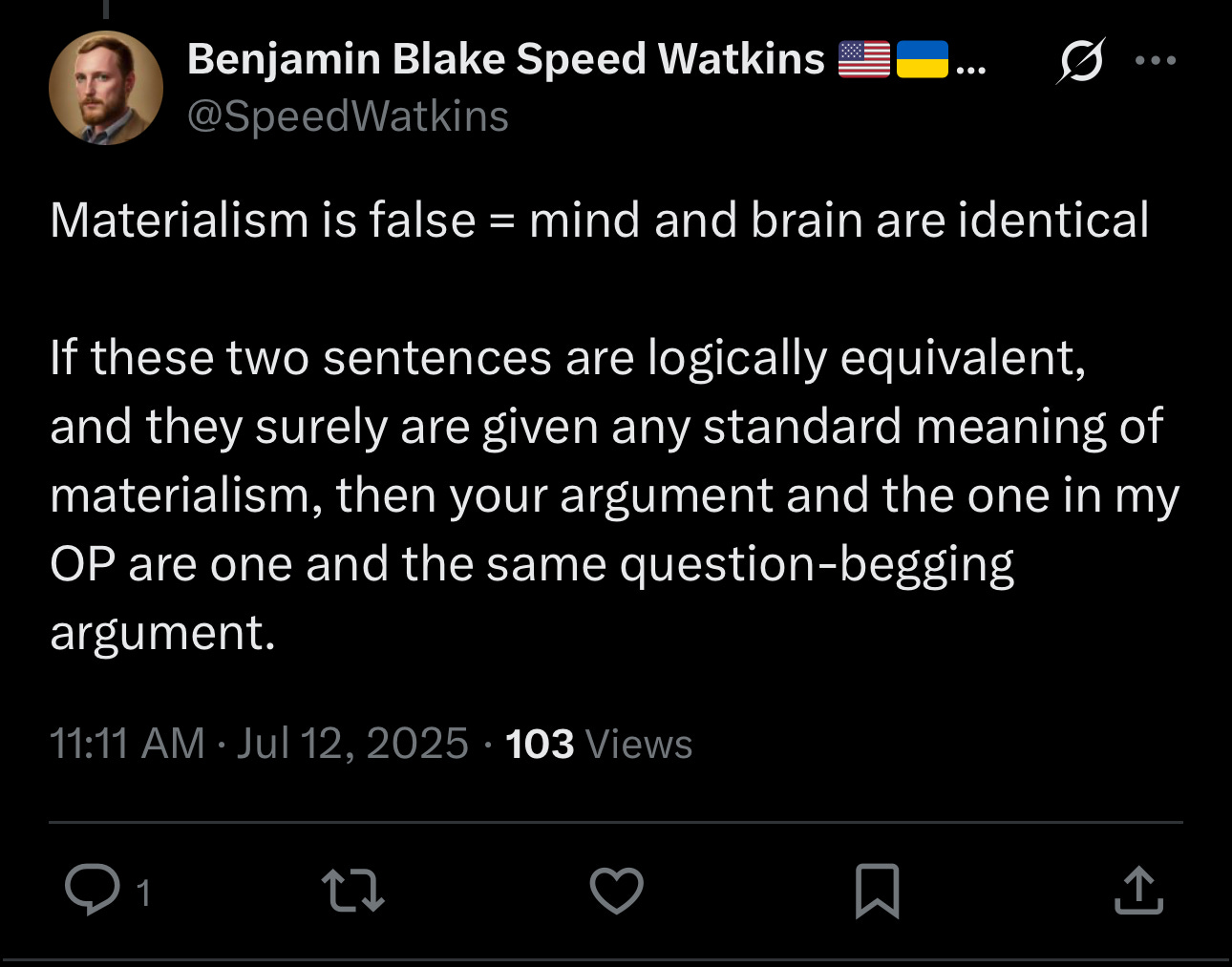

Ok, seems reasonable. But then DtJ hits back with this:

Now, admittedly, the initial reaction one might have to this is: of course! This argument against white swanism is definitely not question begging!

However, Ben is right in this exchange. I’ll be giving a response on his behalf. The reason we are disposed to (mistakenly) think that this argument against White Swanism isn’t question begging is because we all think white swanism is super implausible.

To see this, we need to imagine what a rational person defending it would think. Imagine someone who is a specific kind of theist. He believes in God, but has a different religious text. This religious text has the following verse:

“Verily, do not believe that there are black swans. Your Lord has only made swans that are white, however, sometimes your Lord makes things appear as though certain swans are black. This is for a reason beyond your ken, and to test your faith.”

Let’s also imagine that this religious text, which dates back to 200AD, has been surprisingly accurate: it predicted every weird result from Quantum Mechanics, described in detail the structure of DNA, and has no internal contradictions. Belief in this religion isn’t absurd.

Alright, now imagine you’re talking to the person who believes this. You want to convince him to abandon his white swanism. You trot out the following argument:

(1) If white swanism is true, there are no black swans

(2) There are black swans

(3) So, white swanism isn’t true.

I think it is pretty clear this argument has zero dialectical force. The key premise (2) is literally what is under dispute. You think that there are black swans. He doesn’t. What have we gained from (2)?

Now, you might give independent arguments for (2) itself. You might point out that science has a great track record, or that scientists have isolated a “color” gene in black swans that is different from white swans (idk if this is really true), etc. Now, maybe these arguments won’t work — maybe one’s credence in this religion should be so high that you should just accept that we are being deceived. But these arguments won’t be question begging: they will offer different, independent grounds for coming to disbelieve white swanism. The argument above, though, won’t.

A generally good test for whether an argument moves things forward is this: if a rational person believed ~C, do my premises P1-Pn offer new, independent grounds for C? Am I moving the dialectic elsewhere? Or have I simply restated the issue?

Indeed, instead of calling it begging the question, maybe we should call it “restating the issue”. That might clear things up.

I agree with all this. Though I think a corollary is that whether an argument begs the question isn't something you can straightforwardly read off from the argument itself; it depends on the intended audience. One and the same argument might beg the question against some audiences, but not others. I think that's part of what makes it easy to have disputes like the original one on twitter; people may differ a lot in what audiences they're imagining for some argument.

You assume that begging the question makes an argument bad, but I deny this.

> “Well, even if (2) is false, what makes this a good argument is that it makes dialectical progress.

You assume that good arguments need a possibility of making dialectical progress. I accept that question-begging arguments have no possibility of making dialectical progress. However, your view requires a substantive metaphilosophical assumption that dialectical progress is possible. I am convinced that on many (perhaps most) philosophical issues, dialectical progress is by and large impossible. In other words, there is no way to resolve these philosophical issues through purely epistemic considerations. If dialectical progress is not possible, then it's not obvious that good arguments must even have a possibility of rationally persuading someone who is not antecedently inclined to accept the position.

Second, we rationally do or may hold beliefs based on question-begging arguments. I believe my memory is reliable. Here is an argument to that effect. If my memory is reliable, then I remember a lot of what has happened in my past. My memory is reliable, so I remember a lot of what has happened in the past. I accept this argument, but it begs the question because it won’t convince someone who doesn’t already accept the reliability of memory in general. This argument won’t convince the Pyrrhonist. But if any belief is rational, my beliefs about the past are rational even though they presuppose the reliability of my memory.

> “This is what good arguments do: they move things forward, by showing that there are other, independent considerations that should move you towards my side.”

My concern is that sometimes there are no independent considerations that could move my opponent over towards my side. Think of the radical skeptic, the irrationalist, or the trivialist. If a proponent of these views is sufficiently radical, there will be literally nothing you have in common. The problem with saying that begging the question is bad is that it assumes that you must be able to convince other people based on commonalities. But I deny this. If we cannot we cannot legitimately beg the question against some people, then what do you say to the radical skeptic?